All American Kink Interview by Fred Kaplan

The Gospel According to Artist Celso Junior: "The Only Salvation Is To Yield To The Prick"

1. First, tell us about your name? How prevalent is the name “Celso” and does it mean anything? “Junior” isn’t your surname, is it?

Mmmmmmmm. “Celso” means whatever comes from heaven and its origin is in the word “excelsior,” which signifies the same. Can you believe that? I’m more into hell than heaven, anyway … “Junior” is what distinguishes me from my father, given we both have the same name.

2. When did you decide that painting is how you wanted to express yourself? Are there other artistsin your family? And how did sexual expression relate to your decision to become an artist?

My painting expresses both my desires and thoughts and, above all, my passion for difference. And my reality is sometimes quite difficult, derived from being the kink among the kinks. I don't have any other artists in the family, so my references don't derive from there. I believe [my sexuality] to be mere consequence. I never gave much thought on the subject, but I think in the beginning, both were separated, and only came together later. Today, they are intimately linked and I don't see how to dissociate them.

3. I am assuming that you were raised Catholic. You have been quoted as stating that the “artist is a cursed figure … who is damned for illuminating his tortured existence.” How much has your art been influenced by Catholicism?

My family, Catholic — although not attending Mass or any other religious ritual — is feverous in faith. My parents gave me space for my choices, educating me in freedom in order to discover for myself the price to pay for my acts, and to assume the responsibility of my choices. Undoubtedly Catholicism was a major influence in both my life and work, specifically until my late 20s. In the meantime, I’ve grown the antibodies against this disease, which is the Catholic religion. In fact, I’ve grown antibodies against all religions. There was a period in my life when I deeply questioned myself on this subject. I studied a lot: theology, philosophy and psychoanalytic essays. I read, and read again, La Legende Dorée by Jacques of Voragine, a medieval work that compiles the life of saints. Deep inside my idiosyncrasies that privilege contradiction, I devoured these subjects with both a fascination and repugnance for those unhealthy biographies, replete of the purest masochism, derived from an obvious sublimation of sexuality. The example of Saint Sebastian is flagrant, who, not satisfied in driving himself to self-sacrifice, indoctrinated others to follow him in death. There was a time when I portrayed many men as saints or in their own martyrdom. I no longer have the patience for these implicit references that, want it or not, as a result of being born in Latin countries, impregnate our souls. It’s true that there is a notion, hovering in the air, of a curse, and that we artists are some kind of damned convicts walking always on the edge of things.

Of Catholicism, what remains for me is the architecture of it and every work that resulted from a constant sublimation of the senses over centuries.

4. You were born in San Paulo, but have lived in Lisbon since you were twenty-four. Why did you choose to leave Brazil and what made you choose to live in Portugal?

I was 27 when I moved to Lisbon. My great issue with life or with God summarizes itself in the concept and the truth of FREE WILL.

How was I able to be born in Brazil if my entire imagery was in Europe? I always had the best life conditions in Brazil, but I wasn’t happy for the simple fact of being there. Lisbon was the chosen city because, for me, it’s a privileged spot to keep vigil, and glimpse over an entire Europe without hurting me, a lot. Paris, Berlin and Amsterdam were always my cities of election, but when we decide to live somewhere, we instantly kill the illusions and dreams we built beforehand about that place, no matter how solid they were. For that reason, I decided that a more neutral city would be the ideal to live in, keeping those other cities of my dreams reserved for occasional visits.

The Portuguese men, although dealing constantly, in my opinion, with unresolved sexual issues, are, on the other hand, beautiful. In Portugal, the uniforms of the military forces are a gift to the eyes. In certain fishing towns, you can still find men marked by the hard working life they’ve lead, walking around in the streets with their paved waders.

I guess my greatest pleasure really derives from eternally feeling foreign.

5. I've read that since you were a child, you've acquired more than 250 pairs of boots and you’re quoted as saying that “the best boots are the ones that fit other men … my eyes were made only to appreciate them.” What is your first memory of a man's boots and can you explain the feeling you got from it?

I started collecting boots when I was around 24, 25 years old. As a child, I never owned a pair of boots, and the ones I later bought during adolescence I ended up destroying, for fear or shame of this newly found sensation that I couldn’t really understand.

There were never any military, police, farmers or fishermen in my family, so all my references were external and strange to my environment. When I say that the most beautiful boots are those of the “other,” what I mean is that I constantly seek my object of desire, and possessing it is not enough to satisfy me.

The boots that the other wears will always be more beautiful because my gluttony knows no limits and I assume the pretension of knowing that few people in the world can appreciate them as much as I do.

The beauty and the desire are in my glance. Besides, this intense and insatiable exercise is one of the forms of living my fetish.

As of my first memory of boots, this happened when I was 4 years old, when for the first time in the life I saw a pair of rubber boots in a neighbor’s depot. I remember it so well, and almost 40 years later, I still lively recall both the image and the special sensation caused by the touch, the smell and specially the way I pressed them against my body.

6. What would make a pair of boots ugly to you?

All women’s boots. I assume my misogyny; I hate women using boots, especially if they’re men’s boots. It’s a profanation to my senses.

7. Your art often portrays authority figures, such as police and soldiers. How much do you think the politics of Latin America, where you grew up, contribute to this fetish?

OH YES! They certainly contributed in a decisive way, but they were not at all the source of inspiration for my work.

My imagery is constituted and was built after the colours and violent images of the Spaghetti Westerns and Italian war films of the 60s and 70s. Examples are films directed by Sergio Corbucci such as The Mercenary (1968) and Django (1966), where, in one single sequence, I find all my fetishes combined: BOOTS, UNIFORMS and DEATH. It’s also fundamental to mention Inglorious Bastards by Enzo Castellari (1978), where, from the very beginning to the end, we see Nazis being shot, falling with their legs to the air, exhibiting their high boots. Quentin Tarantino has a project, for 2005, of a remake of this film; I await it eagerly.

Authority figures always fascinated me above all, if they belong to totalitarian armies such as Los Federales, the soldiers in the Mexican army at the turn of the 20th century. With their khaki uniforms combined with high, black leather boots, they provide the right profile and contrast that directly motivates two universes: Underdevelopment and Fascism.

These men, by putting on these uniforms that emphasize their masculinity, become brutalized, arrogant, superb and extremely beautiful — which are characteristic qualities of their army. They lose all human expression, just to become mere objects, ready to die for any illusion.

I can also enumerate some other armies that have a strong effect on me and my art work: such as The German Uniforms, (Wehrmacht, Healthy, and the SS), the great majority of the uniforms of the military police of Latin America, and particularly, those worn by the guerrilla fighters of the FARC of Colombia that tastefully accessorize their camouflaged uniforms with rubber boots. However, this answer would not be complete without the contradictory element that characterizes me: Fascination and Contempt. In spite of giving myself whole to my fetish, I detest all violence perpetrated by those who represent authority, probably men with badly resolved sexual issues who ejaculate with the pleasure given them by this small and illusorily attributed power.

8. What fetish or form of sexual expression have you never approached in your art but have always wanted to?

None. I don't limit or frustrate my fantasy. All elements are present. Just to give you an example, although I’m left wing, I don’t deprive myself of my fetish for Nazi helmets and uniforms. And this is shocking for many people. But above any notion of what is or isn’t politically correct, is my desire. What makes the difference, and certifies my posture as a fetishist and not a racist, is that I have no problem in either painting or fucking a black or Jewish man wearing a Nazi uniform.

9. You've written that you only work from live models. How do you find models and what obstacles exist in finding models in Lisbon because Lisbon is still not considered a European Gay Mecca, is it? Or are you viewed as a celebrity so that there are men who are always eager to pose for you?

Every human being, without exception, one way or the other, longs for immortality. A picture has the power to keep that illusion, at least for one moment. In this game of sensations, it becomes easy for me to seduce the models to pose for me.

I’m no celebrity and this easiness in finding models results merely of seduction games and the vanities of human kind. I don't limit myself to the Portuguese men; I have models of all nationalities. For me, beauty and horniness know no borders.

10. As part of your creative process, do you pose models in actual S/M or other sexual positions? Many of the men in your portraits are in the throes of orgasm? What does orgasm mean to you in addition to the traditional sexual definition?

Yes, definitely.

I pose them in sexual positions. Regarding the series: Death and Transfiguration and Transcendence. All men that posed for me on the verge of, or after, an orgasm, were portrayed as in the instant of death or in its very last second. In my personal progress, where the body aesthetic has always been decisive, I was never convinced or content with conventional standards of beauty or any pictorial or written references.

BEAUTY is an attribute exclusive to the beholder and, in the beauty of sensuality and desire, the only salvation is to yield to the prick. Sentiments and thought are prohibited under threat of being punished by the loss of our erection. Tumescence becomes God and we submit in passion. The theatre, ballet, fine arts, advertising, fashion and cinema — areas in which I have lived professionally since a young age — have always tacitly connived with the tyranny of established canons.

ENOUGH! My penis defines my canon in my selection of models; my tumescence decides the best way to represent them. Academic positions, static or moving, tensing muscles in athletic positions or sensitive lightness of movement as in any choreography, whether it’s a ballet or a tango, leave me completely unaffected; they are commonplace compared with the beauty that the male body exhibits in the act of climax.

Death that comes in a violent form, muscles out of control as bullets definitively break the monotony of the established and present a “figure” in disarray, unstructured, BEAUTIFUL. The facial muscles in particular, go from surprise to pain and finally to the realization of what is definitive, almost loss; this physical lack of control stamped on the face of a macho male superbly reproduces one of our most authentic moments when we permit it: AN ORGASM! DEATH, ORGASM AND TRANSFIGURATION. Three words that define a single moment, one or two seconds, or even a fraction of a second in which we dissolve in a mixture of pleasure, pain and transcendence.

11. While the sexual acts that you portray in your works reflect realism, the colors you choose are generally more vibrant than in reality. What influences your use of color?

It’s atavic. I’m Brazilian, Latin, coloured and I’m sure that the strength and the vibration of my work is in the colour.

12. What is the most difficult thing about capturing the feelings between two lovers?

There is no difficulty; just the opposite.

It facilitates the whole process above all because I’m attracted by threesome male relationships.

13. In “Tapis,” you have three guys: two Tops and a bottom and the Top is inserting a nightstick into the ass of the bottom. Was this painted from reality or was it posed? In other words, do you pose your models or do you capture actual acts in real time?

Both processes are common; they always depend on the atmosphere that builds up and on the interaction between models.

For “Tapis,” it was posed, not meaning that the “game” didn’t continue latter. And that all the energy derived for that “game” wasn’t channelled for the accomplishment of the picture. Don't forget that role-playing is also one of my passions.

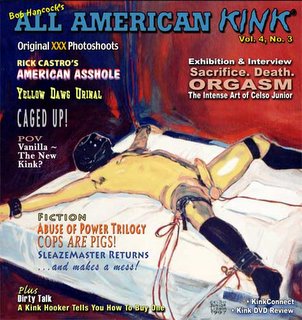

14. “Octávio,” the work — and I assume the model — on the cover of this issue of All American Kink, is very professionally bound. Did you do execute the bondage yourself or is this merely how he was instructed to pose for you? How often do your models get off sexually while posing for you and, how do you feel about it if they do (or don’t)?

NOPE! Here is the reason for such a short answer. I’ve had very few bondage sessions in my life, because bondage is not one of my fantasies, not as bottom, nor as Top. However, being as curious and extremely voyeuristic as I am, I gave myself — body and soul — to those few experiences. Octávio (Portuguese) was the third element in a session with a Master in bondage (American), and unlike “Tapis”, it was done in real time.

15. Your statement, “I never paint thinking about other people,” is truly provocative. Does that mean that you don’t take commissions for new work?

I’ve already created many works on commission and I am never closed to this type of proposal. But I recognize that a commission can generate a painful and difficult process, in comparison with a painting that is born and executed solely driven from my desire.

When I state that I don't paint with the “OTHER” on my mind, what I mean is that the selection of my models and themes emerges from my horniness and from the foreseen pleasure that I want to take out of it, and not from the possibility to create something desirable for the OTHER, and to consequently create a work that is more easily marketable.

16. How is the process of painting a landscape different from that of painting a sexual image? When you exhibit your work, do you include your landscapes along with those that contain sexual imagery?

I’ve painted many landscapes and sold them all, but the pleasure in making them is zero. They are worthy as formal studies and experiences on colour mutations. I don't even have the desire to exhibit them — notice that the very background of my pictures is, in their majority, neutral or with interior scenes.

What I really like to paint are portraits because I can touch the soul of the models and always bring to light something that is hidden, or in latent potency, something that they have still not discovered or manifested. And since it is almost impossible to dissociate sensuality from the human figure, the final picture comes up with a strong sexual appeal.

17. In addition to painting, you are a photographer and video producer. Which of these forms the basis of how you earn your livelihood? And I’ve also read somewhere that you own 25,000 fetish photos! Can this be true?

All these professions are exclusively linked to survival. Now there are about 60,000 photos and it’s an ever-increasing number. They are compilations, newspaper and magazine pictures, and about 12,000 taken by me. The point in common among all: MEN WEARING BOOTS!

18. You are credited with starting the Lisbon Gay and Lesbian Film Festival when you improvised a retrospective of gay films by screening your personal videotape collection. How important do you see film and video in your future and how will it affect your relationship to painting?

I created the Lisbon Gay and Lesbian Film Festival — it is already undergoing its 8th edition — and I remain its director and programmer.

This retrospective to which you refer was presented in the Festival’s 1st edition, in 1997, and it was decisive in solidifying both our public's regular attendance, and the support of our sponsors. As I already said previously, cinema is my main source, and from which I’ve built my imagery. Cinema and video assume a crucial importance in giving life to something that the painting limits: THE MOVEMENT.

I have many projects for video (SHOTS) and I’m planning to accomplish my first documentary: TALKING ABOUT RUBBER BOOTS AND MACHINE GUNS, where I will tell in images the depositions and experiments of several fetishists, without ever justifying them.

19. You are involved with John Scagliotti, the gay American documentary filmmaker, on two new documentaries. Tell us more about this.

I already invited John twice to present his documentaries (After Stonewall and Oliver Button Is Star) in Lisbon and this year he will come for the third time. John is a sensitive man and has the talent to perfectly marry cinema and LGBT activism. As for my involvement with John’s latest documentaries, on his last visit to Lisbon, he was working on them, interviewing many people, so I just helped him out on whatever I could, contacting people, etc.

20. You’ve exhibited your paintings in many European cities. Where do you find that your work is most appreciated and by whom? How come, other than the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles — where you are a “Permanent Artist” — you’ve shied away from promoting your work in the US?

Hard to tell, I guess Paris, where besides some exhibitions, I’ve been represented by a gallery. If someone invites me to exhibit my work, normally it’s because they truly appreciate it.

There is no middle term, people hate or love my work and I believe that what I do is hardly commercial.

The Tom of Finland Foundation called me after seeing my work at Greasetank.com, an artist with whom you’re quite familiar.

[Editor’s Note: The artist, known as Greasetank, was interviewed and featured in AAK, vol. 3, no. 4.]

No, no one represents me in the US. Yet.

21. You exhibit your work online on several different gay art web sites? What thought have you given to creating your own site to promote your work in diverse media?

I’m a disaster on taking care of myself. It’s very difficult for me to deal with the commercial part of my work. In fact, I’ve always wanted to find a tyrannical manager that would rip me off — honestly — and exploit me in every sense!

22. Is there a typical aficionado of the work of Celso Junior? And what is the best method for collectors to contact you regarding purchase of your work?

If there is any “typical aficionado,” just come by my house. As for the second question, just e mail me.

23. So whom did you have to fuck at this magazine to get this interview?

Not really. What a pity … Well, I’m not averse to this occurrence, nor limited by distance. Just put your boots on.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home